People Plants & Revolution

– Faries Gray, Sagamore (War Chief) of the Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag

– Miranda Lachman of Lexington Community Farm

– Climate scientist Bill Moomaw, Ph.D

– Culinary historian Sarah Lohmann

– Foraging expert Russ Cohen

– Landscape historian Patrice Todisco

– Arlington journalist and volunteer Crystal Haynes Copithorne

– Banner artist Liz Shepherd

– Plant biologist Dr. Molly Edwards

MASSACHUSETT LAND

The area that we currently call Arlington was a part of the lands of the Massachusett people, which included present day Boston and extended north to Salem and south towards Marshfield. The last leader of the Massachusett tribal settlements living north of the Charles River is known only by her title, Squaw Sachem, as she chose not to give the English her name. We recognize that the use of this title is considered offensive by some, but it is the name that the Massachusett at Ponkapoag use to tell their story. By the 1630s, 80% of her people had died of disease or violence, including her first husband and her two sons, both tribal leaders as adults. Although a skilled leader, her power had been diminished by this overwhelming loss of people. She had few options but to negotiate with the Colony. In 1639 she signed an agreement giving Charlestown settlers use of a large territory, but preserved part of Menotomy south of Mystic Lakes for her lifetime for “the Indians to plant and hunt upon, and the weare above the ponds…for the Indians to fish.”

An edited transcription of our conversation with Faries Gray, Sagamore (War Chief) of the Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag, will be posted here soon.

INTRODUCTION / DANDELION

This banner features a dandelion, a familiar plant that was originally imported from England and valued as food and medicine. It escaped colonial gardens and has spread into green spaces throughout North America. For many it is an annoying weed. Others relish its beauty, enjoy its tasty green leaves, or drink dandelion tea!

“Today plants are often out of sight; in Menotomy plants were in full view. An early frost, a blight, new cuttings from a neighbor or seeds from a ship were transformative at a time when you could not go to a corner store for food.”

Welcome to People, Plants & Revolution, a multimedia public art project organized by Cecily Miller for ArtsArlington to commemorate the 250th Anniversary of the American Revolution in Arlington. We explore colonial life and some of the stories, legends, and history surrounding the revolutionary events of April 18 and 19, 1775 – all through the lens of plants. At that time, Arlington was a farming village of 500 to 600 people and plants were all important! Officially part of West Cambridge, it went by Menotomy, adopted by the colonists from the name “Menontamumat” used by the Massachusett tribe – the original people of this region. We use Menotomy throughout this project, which consists of colorful banners designed by a collaborative team of four artists and an audio tour combining many voices and perspectives. The artists – Liz Shepherd, Suzanne Moseley, Lily McDonald and Andrew Palladino – created multilayered silkscreens combining colonial-style images with plant illustrations from the Harvard University Herbaria. The blue background is inspired by the blue of cyanotype chemistry, used since the 1840s for botanical illustration.

This project explores the ways that plants are part of both the natural and the human world. The people of Menotomy – both before and after the English settlers arrived – were shaped by the plants around them, and in turn transformed those plants through cultivation and use. Indigenous peoples used fire to shape forests, collected plants from far away through trade or travel, and grew their favored food plants, all while promoting values of sustainability and relationship to nature. Colonial settlers brought plants from England to recreate a familiar way of life and fulfill a longing for home, reshaping the ecosystem around them. They also exported plants back home as needed, and traded plants back and forth throughout the British global empire. One perspective underlying the colonial enterprise was that nature is a resource for extracting commodities for sale as much for survival. In Menotomy however, people planted to create subsistence farms that would fulfil their family needs and give them the independence they cherished.

Today plants are often out of sight; in Menotomy plants were in full view. An early frost, a blight, new cuttings from a neighbor or seeds from a ship were transformative at a time when you could not go to a corner store for food. Colonists knew that they depended on the plants that grew around them – whether wild or cultivated, native or brought from England to recreate a familiar way of life and fulfill a longing for home. Contemporary Arlington is home to many passionate gardeners and environmental advocates, but in general fewer of us live in close relationship with the land or get our hands in the dirt. We hope that this project encourages people to engage more deeply with what grows around us.

In the course of learning about the plants of colonial Menotomy, we have been confronted with the suffering and devastating erasure of the original people, the Massachusett. They lived on the coast from Salem to Plymouth and inland west as far as Worcester. The Massachusetts Bay Colony’s 1629 royal charter empowered English settlers to “to reduce or convert to submission the indigenous people of New England,” and the settlers did so. The Massachusett were forcibly removed to make their land – including their planting fields and forests – available to English colonists.

Despite these losses, the Massachusett have not disappeared. They are still here. We are grateful to the leaders of the Massachusett at Ponkapoag for sharing the Massachusett story with us. We honor their vision of the land as a place that rightfully shelters and sustains all who care for it.

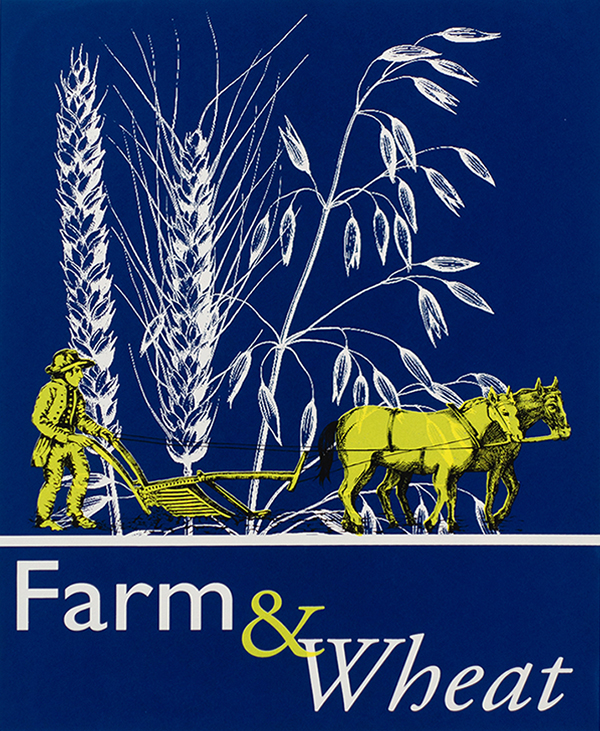

FARM / WHEAT

Welcome to the farm and wheat banner, which shows a colonial farmer and two horses plowing a field. Larger-than-life ears of English wheat and oats rise up behind them.

A typical colonial farm in Menotomy was self-sufficient, producing enough to feed the families that tended them and securing the independence that was every settler’s dream.

The first farmers in Menotomy were indigenous Massachusett women, who owned fields planted with a variety of crops and passed down from mother to daughter. Their fields looked quite different from the straight rows used in English farming. They used a hoe rather than a plow and the complementary “three sisters” crops – corns, beans and squash – were planted in large mounds, growing together, cooperatively intertwined.

By 1775, Menotomy was home to 500 to 600 people, primarily of English descent. Land had been passed down, subdivided, and sold multiple times. Some of the farms had been owned by several generations of a single colonial family. Others were owned by newcomers, and a handful were rented out to tenants. Decimated by generations of disease and war, few indigenous people remained. However, one – David Lamson – is honored as one of the heroes of April 19. Lamson led a successful ambush of a British supply wagon that had fallen behind the troops. He went on to serve in the Continental Army and was last known to be living in Charlestown, listed in the 1790 census as “resident and free man.”

A typical colonial farm in Menotomy would consist of a house and fenced kitchen garden, crop fields, an orchard, barn yard, and pasture area. These were self-sufficient farms, producing enough to feed the families that tended them – securing the independence that was every settler’s dream. Some farmers would grow enough to load up a wagon and make the trip to Boston, selling produce in order to purchase luxury items. But it was more typical for farmers to barter with a neighbor for something they needed.

What did colonial farmers plant in 18th century Menotomy?

Native corn remained a primary staple from early times. Field vegetables could be a mix of old and new world varieties, including potatoes, squash and pumpkin, root vegetables, kidney and navy beans. These could be pickled or simply stored in a cellar to meet the household winter needs. English rye and wheat were cultivated for flour and barley was grown for beer. The Black Horse Tavern, where rebel leaders met on April 18, would surely have served up its own brew, possibly along with some rye whiskey.

Just as essential, farmers grew food for their animals – oats, alfalfa and clover. A colonial farm was not complete without cows for dairy as well as meat, pigs, sheep, and chickens. Horses helped with plowing, pulled wagon loads, and provided transportation. Manure from the farm’s animals helped fertilize soil depleted from crops.

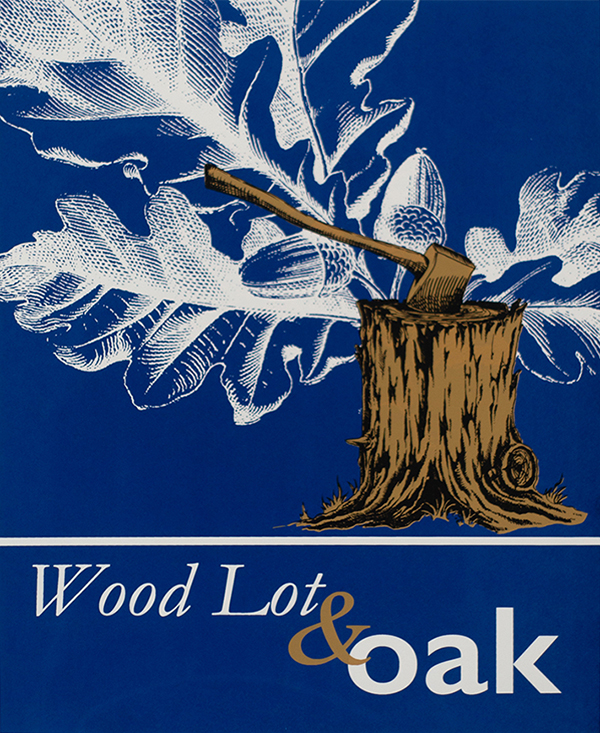

WOODLOT / OAK

Welcome to the Woodlot & Oak banner, which depicts a cluster of broad, lobed oak leaves and large capped acorns behind an oak stump with a hatchet buried in it.

Wood from oak trees had many familiar uses, from building houses and boats to barrels and tools. More surprising: the Declaration of Independence was written with ink made from oak gall.

Before the English settlers arrived, the Massachusett people maintained Menotomy’s forests. They cleared some land for farming and harvested trees for practical use – including building their homes, mushoons, and a traditional long drum. But they had a strong interest in preserving forest as forest, because that ecosystem supported the plants and animals that all life relied on.

Early settlers also foraged and hunted in the woods, but preferred food from their farms. Forests were more important for lumber, a valuable commodity that could be exported back to England – which was largely deforested at the time. But Menotomy’s trees were reserved for more local use, and trees were cut down as wood was needed. Convenient woodlots provided fuel to keep warm in winter. Trees were used to make nearly everything. Fences, barns and houses. Furniture, utensils and tools. Spinning wheels and plows. Wagons and wheels. Barrels for storing or shipping staples from cider and beer to flour and salt pork. It’s not surprising that by 1745 big trees were becoming scarcer. That’s when Menotomy farmer Jason Russell built a new family home re-using massive oak timbers from his grandfather’s 1660 house to augment wood from remaining oak trees on his property. Oak trees had other uses; ground acorns are nutritious and the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution were written with ink made from oak galls.

During the 1775 Battle of Menotomy, Jason Russell would lose his life fighting in the front yard of his home. But Menotomy’s wooded areas provided crucial shelter for other colonists using the guerilla-style warfare which proved effective in the fight against the world’s most powerful army. “The country people,” as the British called the rebel fighters of Menotomy, took positions behind trees to shoot with deadly accuracy at the exposed British column as it marched in retreat back to Boston. Lord Hugh Percy, the Brigadier General in charge of these royal troops observed:

“Whoever looks upon them as an irregular mob will find himself very much mistaken. They have men amongst them who know very well what they are about having been employed as rangers against the Indians and Canadians, and this country being much covered with wood and hilly is very advantageous for their method of fighting.”

He was – however reluctantly -- impressed by the “perseverance and resolution” of the country people of Menotomy and beyond.

ORCHARD / APPLE

Welcome to the Orchard & Apple banner. It features a man in colonial dress carrying a basket of apples to a cider press.

A popular colonial apple was the Baldwin, popularized by a veteran of the Battle of Concord. The Baldwin and other varieties, including “spitters” too sour or mealy to eat, were made into cider, the most popular drink of the time.

The legends surrounding the events of April 19 contain one evocative reference to Menotomy’s farmhouse orchards. Alerted to the approach of British troops and fearing violence, women and children were sent to places of safety outside the village. Many took shelter at George Prentiss’ house on a hill removed from the main road. From there, they could doubtless see the smoke of burning homes and hear gunfire. One of them – Mrs. Lydia Pierce – recalled her childhood memory from that terrible day. More than 80 years later, she described the beauty of the orchard’s peach trees in bloom. Perhaps the trees in some way offered a feeling of comfort and sanctuary during a time of terror.

17th century explorers and colonists brought English fruit trees and seeds with them to plant in New World soil. Perhaps they too were comforted by pears, plums, peaches and apples – familiar fruit in a strange world. These transplants did well. By the 1720s, Justice Paul Dudley boasted about his Massachusetts trees: “Our peaches do rather excel those of England, I have had in my own Garden seven or eight Hundred fine Peaches of the Rare-ripes, growing at a time on one tree.” He recounted the success of his neighbor’s “Bergamot Pear Tree…brought from England in a Box, about the Year 1643” which had flourished after its long voyage and would yield “twenty-two Bushels of fine Pears in one Year.”

The fruit that perhaps had the greatest success in the New World was the apple. Apple seeds carry an astonishing genetic diversity and new varieties emerged rapidly, adapting to local soil and climate conditions. Of the thousands of New World varieties, some became famous. One of the most popular was the Baldwin, originally discovered growing wild in 1740 by a farmer in Wilmington, MA. It was distributed all over New England using cuttings from the original tree by Loammi Baldwin, coincidentally a commander of the Woburn regiment during the Battle of Concord.

The Baldwin and many other varieties, including “spitters” too sour or mealy to eat, made wonderful cider. Fermented hard cider was one of the most popular beverages for colonial people of all ages. On April 18, the Committee for Safety – a core group of rebel leaders – met at Arlington’s Black Horse Tavern. Perhaps cider or the stronger proof apple brandy sparked some of their revolutionary spirit?

PASTURE / CLOVER

Welcome to the Pasture & Clover banner. A Colonial farmer is busy repairing his pasture fence, and an English clover plant in bloom forms the background of the image. Each leaf is divided into a delicate cluster of three leaflets.

Paul Revere on horseback is an iconic image from the stories of April 18 and 19, 1775. Fenced pastures were essential to the swift horses that alarm riders used to alert the colonists that British soldiers were on their way.

Paul Revere on horseback is perhaps the most iconic image from the story of April 18 and 19, 1775. Revere, Willam Dawes, and many other riders formed a network that spread the “alarm” that the British were on their way. Swift and sturdy horses were essential to gathering men from a 30-mile radius overnight into a force of over 3,500.

Menotomy’s fenced pastures were essential for keeping horses, as well as cattle, sheep and oxen. All these animals were originally imported from England to continue a way of life centuries old. In addition to transport, they provided staples for the household – including butter, cheese, meat and wool. They helped small farmers generate profits which could be used to purchase European goods or more land. And they radically transformed the native ecology of New England fields.

Before colonization, indigenous people did not keep livestock or fence areas for specific uses. Native grasses, wildflowers and shrubs were not exposed to intense grazing down to their root structure. The settlers’ pasture system – enclosing livestock in small spaces – decimated diverse ecosystems, impacting butterflies, moths, insects, birds, snakes, lizards, and other small animals that depended on native plants.

The colonists reseeded bare fields with the plants of an English pasture when they realized that native plants did not provide the nutrition that livestock needed. At first, English seeds spread on their own, transported along with feed and bedding. But by the 1760s seeds were commercially available and promised the hardiness, nutrition and visual appeal of the English meadows of home. These species, including clover, have become so pervasive over 250 years that we perceive them today as part of the natural landscape rather than an invasive species.

Almost a hundred years after the events of 1775, Henry David Thoreau made a close study of the remaining native grasses and wildflowers in neighboring Concord. He collected specimens of plants that were once ordinary and are now rare; these are preserved by the Harvard University Herbaria, a research collection of over 5 million dried pressed plant specimens. Thoreau also closely observed seasonal changes in plants and kept meticulous daily field notes. His data are still being used by modern scientists to measure and study the impact of climate change on the living landscape.

Today, whether English meadow or native grassland, much of the green space in Arlington has been built over. Neighborhood parks still give people great pleasure, and there is a community effort to restore native plants in these spaces and in backyards to protect pollinators and wildlife and increase environmental resiliency as we face the challenges of the 21st century.

KITCHEN / GARDEN

Welcome to the Kitchen Garden banner, which shows a colonial person carrying a basket through their small fenced garden, sowing seeds as they go. Root vegetables decorate the background, a vision of what is to come.

A successful merchant, such as John Hancock, had a formal garden enhancing his mansion home. But for average people, English vegetables, salad greens, and herbs prevailed in a kitchen garden, with peas leading the way!

Almost every home in the 1770s had a kitchen garden – a large practical planted area convenient to the kitchen door. The useful plants in these gardens had crucial jobs to do: feed the family, season or preserve meat, pickle vegetables, prepare or dye textiles, help with cleaning or laundry, sooth a lingering cough.

Although there are fine examples of 18th century architecture preserved in the Arlington landscape of today, Menotomy’s colonial gardens have not survived. Arlington’s Garden Club has recreated a colonial kitchen garden with 36 useful herbs and flowers at the Jason Russell House. For vegetables, we can look to the records of Boston’s pioneering nursery men and women as well as importers of seed and stock. According to one study: “London dominated every aspect of Boston’s horticultural life throughout the 18th century as did the overwhelming English character of food tastes and ornamental gardening.” For successful merchants, such as rebel leader John Hancock, this London taste translated to enclosed formal gardens with geometric beds and espaliered trees adjoining a showy mansion. But for average people, English vegetables, salad greens and herbs prevailed, with peas leading the way! In addition to an astonishing 20 varieties of peas, other staples – each with its own subvarieties maturing at different times -- were beans, cabbage, and lettuce. Next in popularity came carrots, cauliflower, parsley, spinach, onions, radishes and turnips. Celery, asparagus and melon were also given space in raised rectangular beds, along with a selection of herbs. A skillful gardener living in a rural community like Menotomy could also bring plants foraged from the wild into their fenced backyard. Why not tame a sweet strawberry or bitter green and have it ready to hand?

Women and children tended the kitchen garden while men focused on larger planting fields. Some Menotomy families had extra hands to help – including enslaved and free people of African descent. Information about Menotomy’s enslaved residents is scarce and fragmentary, but local historian Beverly Douhan has uncovered records of 11 women who lived there around the time of the Revolution. It is likely that these women helped to tend kitchen gardens along with other household work. All we really know is their names, so we say them here as a way to remember them: Kate, who lived with the Jason Russell family, Rose and her daughter Venus, Dinah, Flora, Pegg, Dinah, Flora, Nancy, Violet and Hannah.

COMFORT / SOAPWORK

Welcome to the Comfort & Soapwort banner, which celebrates the ways plants could improve a home. Two hands dipping into a basin are surrounded by soapwort, used for all purpose cleaning.

With its multiple uses it is little surprise that humble soapwort was common in the colonies; it was used to wash everything, including clothes, dishes, hair, and even the wool of sheep before shearing.

Many of the plants found in the recreated colonial garden at the Jason Russell House eased ordinary hardships. Sweet William, sweet woodruff, and rosemary were strewn on floors to improve the smell of an 18th century home, and aromatic plants were made into pocket sachets or put into soap and bathwater. Feverfew and santolina repelled mosquitos and moths. Clove pinks flavored wine, ale, syrups, sauces and jams. Chervil was believed to combat the winter blahs and elecampane to cure melancholy.

For the comfort of keeping things clean, humble Soapwort, was a winner. A long-lived perennial that spreads prolifically, Soapwort (Saponaria officinalis) can still be found blooming freely along roads and fields. It can be recognized by its clusters of small flowers, each with five delicate petals. While it is sometimes classified as a noxious weed, this phlox-like flower has been cultivated in gardens for centuries.

When crushed, Soapwort’s leaves and stems create a lather; its boiled roots produce a detergent which can dissolve grease. In its mildest form, it was historically used to clean delicate fabrics and wool tapestries. It contains fungicides that aid in the preservation of cloth. Recorded in England as early as 1540, soapwort’s nickname “Bouncing Bet” references the English washerwomen and barmaids who used the plant to clean beer bottles.

With its multiple uses it is little surprise that this humble plant was common in the colonies, where it was used to wash everything including: clothes, dishes, hair, and even the wool of sheep before shearing. In testimony to its versatility, its leaves could even be used to enhance beer’s foamy head and in the treatment of poison ivy, rheumatic disorders, and intestinal infections.

Today, soapwort is listed in the Invasive Plant Atlas of the United States. A garden escapee, it spreads through an extensive rhizome system as well as by seed. As a result, while it is not commonly planted today, it still can be found throughout New England, a reminder of our colonial past.

DELIGHT / HOLLYHOCKS

Welcome to the Delight & Hollyhocks banner, which represents the medicinal use of hollyhock with a tincture bottle as well as the pleasure of its flowers.

Symbolizing growth and rebirth, the hollyhock is a fitting emblem for the Puritan settlers. Fleeing religious persecution, they sought a way to live closer to their god in the new world of New England.

What was the role of beauty and delight in decisions about what to plant in the gardens of colonial Menotomy? Historian Ann Leighton offers a comprehensive list of the many practical services provided by early New England gardens, from flavoring and preserving food to aiding in childbirth and laying out the dead. And yet, she observes “all of these plants, useful and dull though they may sound, were capable of bursting into fragrant bloom to make gardens gay and pleasant spots.” Some reliable self-sowing favorites, according to Sturbridge Village, were sweet William, pot marigold, blue bottle, alyssum, and sweet violets.

On July 26, 1631, John Winthrop, the Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and an avid gardener, placed an order to Robert Hill in London, requesting more than 50 varieties of seeds. Included in the bill, found in the records of the Massachusetts Historical Society, are the seeds of ‘hollihocks’, a popular plant in Europe with striking flower spikes full of hibiscus-like blooms. All parts of this plant are edible; the colonists made tea from its flowers and valued its roots for their multifaceted medicinal purposes. And hollyhocks had history and meaning as well as charm and utility.

Originating in Asia, hollyhocks are credited with being brought to England from the Middle East during the Crusades with its name, holihoc, a combination of ‘holy’ and hoc, the Anglo-Saxon word for a mallow, as they are part of the mallow family. Symbolizing growth and rebirth, the hollyhock is a fitting emblem for the aspirations of the Puritan settlers led by Winthrop. Fleeing religious persecution, they sought a way to live closer to their god in the new world of New England.

From 1880 to 1930, the popularity of the hollyhock reached its apex during a period known as Colonial Revival. Designers used its graceful form as a motif in the decorative arts. During the two hundred fifty years since its introduction into the New World, the hollyhock has been bred to produce larger flowers, a wide range of brilliant colors, and double blossoms. A prodigious self-seeder, it has become ubiquitous in the New England landscape as a poignant reminder of its early origins.

MEDICINE / AJUGA

Welcome to the Medicine & Ajuga banner. It shows a spike of Ajuga flowers sandwiched between equally ornamented leaves, with a mortar and pestle to represent its healing properties.

When a red-coated soldier knocked on the door to investigate, the wife claimed that she was merely making an herb tea to treat her husband’s illness, a convincing story because women routinely used the herbs grown in their gardens to treat family ailments.

Volunteers from the Arlington Garden Club recreated a colonial garden at the Jason Russell House. Most of the 36 plants listed in their guide serve multiple purposes. Tansy, for example, was used to treat worms, aid digestion, repel insects, and embalm the dead! While such versatility was desirable, healing properties were essential for households facing infectious diseases, injuries, and difficult births.

On the night of April 18, 1775 a Menotomy couple was melting their pewterware in their fireplace to reshape the metal into musket balls for the rebel militia. The story goes that the light in their window raised the suspicions of the British regulars marching by late at night on their way to Lexington. When a soldier knocked on their door to investigate, the couple hid the evidence. The wife claimed that she was merely making an herb tea to treat her husband’s illness, a convincing story since much routine healing fell to women using ingredients from their kitchen gardens.

The battles fought in Menotomy on April 19 are considered the bloodiest of that fateful day. Another plant found in the Jason Russell House kitchen garden is Ajuga, which was grown purely for medicinal purposes. Ajuga was thought to stem bleeding and its leaves could be used as bandages. A doctor worked to save the most severely injured, but local women also provided nursing care. Perhaps ajuga was used by the women of Menotomy to treat fallen fighters.

Another story from April 19 records the actions of Mrs. Butterfield. She returned home after the battle to find her best bed covered with blood and occupied by an injured British officer; a wounded militia man was in the next bed. She cared for both using her own resources as well as supplies that were brought for the officer from Boston under a flag of truce. In addition to ajuga, comfrey, hyssop, yarrow and sage could have been useful for treatment. All are found in the Jason Russell House garden today. The patriot recovered but the officer did not survive despite Mrs. Butterfield’s sincere efforts.

PROTEST / FLAX

Welcome to the Protest & Flax banner, which shows flax flowers with their five broad petals surrounding a colonial woman at her spinning wheel, perhaps participating in a spinning bee protest.

Public spinning bee were organized as popular protests throughout the colonies. Participants were expressing their patriotism and resistance to royal tyranny. One farm girl even reported that she felt “nationly” after spinning.

Colonial women had limited rights and little voice in official public life. However, rebel leaders welcomed their wives, sisters and daughters to partner in the struggle against tyranny with a visible boycott of British textiles. This is how flax became a hero of the Revolution, and women participated in the rhetoric of liberty and equality!

In the 1760s, the British government had heavy debts from a series of wars. To solve their financial problems, the King and Parliament imposed new taxes on the colonies. In retaliation, the colonies organized voluntary boycotts of British imported goods, especially textiles.

To replace banned textiles, colonial women made homespun linen using locally grown flax. The spinning wheel became a symbol of freedom from royal tyranny. Public Spinning Bee protests became popular throughout the colonies. Women participating felt like patriots, and a Connecticut farm girl reported that she felt “nationly” after spinning. We don’t know how this played out in Menotomy, but we do know that an impressive public Spinning Bee was held in neighboring Lexington. Twenty-nine year old Anna Harrington gathered 45 women on the grass outside her home, and given the connections between the towns it is easy to imagine some Menotomy women joined in to demonstrate solidarity with rebel leaders.

Although not a native plant, flax would have been easy to grow in Menotomy and Lexington. However, preparing the strong stalky fibrous plant for spinning was strenuous and required specialized tools. After dried flax stalks were broken and separated on a flax brake, the fibers were “scutched” or “swingled” to remove remaining bark. Fibers were then pounded and repeatedly “hackled” – pulled through a sharp comb called a hackle – to remove chaff and detangle the fibers until they resembled fine blond hair.

Records of the daily lives of people of African descent in colonial times are scarce but the Lexington Historical Society uncovered a glimpse of a local emancipated couple, Prince and Cate Chessor, who earned extra money using their skills preparing and spinning flax. The town’s minister, Reverend Jonas Clarke, paid them to do this work. He also baptized their daughters, Ruth and Lucy, before the family moved to Boxborough in 1777, where they had five more children, owned land, and prospered.

Many thanks to historian Catherine Allgor for sharing the story of farm girl Betsy Foot – who felt “nationaly” after spinning – during an interview on the Culture Show.

VOYAGE / TEA

Welcome to the Voyage & Tea banner, which features an illustration of a colonial sailing ship and the tea plant grown in southern China and shipped around the world.

Tea became one of the world’s most desirable plants and was shipped around the world to satisfy cravings for a sophisticated stimulant and elegant tea parties. The British tax on tea inspired one of the most theatrical protests in American history.

The Boston Tea Party is one of the iconic events of the American Revolution. Colonists angered by tax policies imposed by an absolute monarch and a parliament where they had no representation dumped tons of valuable tea into Boston harbor. One of the world’s most desired plants, the tea had just arrived from China. Its long voyage was undertaken to satisfy cravings for a sophisticated stimulant that was a focal point for social gatherings and a ritual of daily life. How many in Menotomy were addicted to this plant by the time of this theatrical protest against autocracy? At that time, colonists drank 1.2 million pounds of tea every year!

In 1773 the British government gave the British East India Company a monopoly on the importation of tea to the colonies, cutting out local merchants such as John Hancock. On top of this, Parliament retained a tax on tea after dropping other controversial taxes on imports. These actions were pronounced to be tyranny and a band of patriots carefully planned the Tea Party as a highly visible – although anonymous – protest to send a message to the crown. Next they took a radical stand: they refused demands to pay compensation. In heavy-handed retaliation, England passed the “Coercive Acts.” These included suspending local government, doubling the troops occupying Boston to 4,000 soldiers, and closing Boston harbor to all commerce. No ship could come in or out, including those carrying tea.

The reverberations of these events were felt in Menotomy. Tensions that had been building for a decade between King, Parliament and rebel leaders came to a head on April 18, 1775. Royal soldiers marched through Menotomy on a mission to seize military stores in Concord but things got out of hand. They provoked an uprising that swelled and spread and a rebellion was well and truly launched the next day.

Closing Boston’s harbor was a local calamity. Ships transporting and trading goods were the engine of the region’s wealth. Salt pork and fish produced by local farmers and fisherman were shipped in barrels to sugar plantations in the West Indies, and textiles and luxury goods arrived regularly from Britain. But the most lucrative cargo in the Atlantic trade was enslaved human beings. The first of many thousands of enslaved African people arrived in Boston aboard a ship named Desire in 1638. Over the next 130 years Massachusetts ships would also send indigenous people captured during colonial wars to enslavement in the West Indies, often returning with enslaved Africans. Fighting in the American Revolution – on either the British or colonial side – was one way enslaved people could secure their freedom. There was a substantial population of free people of color in 18th century Massachusetts, including abolitionist Prince Hall, whose petition to the Massachusetts Legislature pointed the way to the new Massachusetts Constitution. Passed in 1783, it wrote the ideals of freedom for all promoted during the American Revolution into law, providing the basis for Quock Walker and other enslaved people to free themselves by challenging their status in court.

The unjustness of tea taxes was one of the triggers of the American Revolution, and while liberty for all prevailed in Massachusetts shortly after, it would take nearly another century for the unjustness of enslavement to trigger a civil war.

CULTIVATE / CORN

Welcome to the Cultivate & Corn banner. It illustrates two men in colonial garb picking corn in a fenced field.

On the night before April 19th, 1775, three rebel leaders hid from British red coats in a Menotomy cornfield. At the beginning of colonization, indigenous people taught Puritan settlers how to grow this nutritious grain, saving them from starvation. Corn became a staple and was cultivated in Menotomy’s 18th century farms.

In April, 1775 Boston was under military occupation and no longer safe for rebel political meetings. Nearby Menotomy offered an ideal alternative. Major roads connected it with other towns. Its residents were supportive and its minister preached fiery opposition to royal tyranny. Fifty militia members mustered for battle under command of Captain Benjamin Locke. Notably, this militia included two Black patriots, Cuff Whittemore and Cato Wood, who continued to fight after the first battles in Lexington, Concord, and Menotomy.

On April 18, a group of key rebel leaders convened at Menotomy’s Black Horse Tavern and three remained overnight. Marching in darkness towards Concord, something prompted a group of passing British soldiers to stop and search the Black Horse Tavern. Roused from their beds by the tavern keeper, the three leaders fled out the back door. There was nowhere to hide in the moonlight except a field of corn-stubble from the previous fall. They threw themselves flat on the ground, and, remaining still overnight, escaped uncomfortable questions or worse.

And so, we get a glimpse of Menotomy’s colonial agricultural landscape. The inn, also a home and farm, sat surrounded by harvested corn fields. Massachusett people taught English Puritans how to grow this nutritious grain, which could flourish in the poorest soils, saving them from starvation. Corn immediately became a staple. Some historians believe that the colonization of North America would have failed without this transfer of knowledge.

In the earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, planting a field was understood by Puritan founders as the virtuous way to establish ownership of land. In 1630, farming was not only a European settler’s means for survival, it was also the cultural and legal justification for displacing native people and denying their land rights. Colonists believed unplanted land – forests, meadows, and foraging areas – was wasted land, and even a Christian sin. This worldview kept leaders like Governor John Winthrop from seeing the beauty, intelligence, sustainability, and spiritual stewardship of native land use even as he praised the splendid abundance of the New World. For tens of thousands of European settlers, farming was a way of escaping poverty through hard work and knowledge. At the same time, genocide and forced displacement of native people were the foundation for the settlers’ secure way of life.

And so we return to the image of three revolutionary leaders taking shelter in a corn field that was planted using Indigenous knowledge passed down from early settlers. We can simultaneously acknowledge their courage in the face of a tyrannical colonial superpower, and that they were fighting for and claiming land that was not theirs to begin with.

And today, our nation continues to grapple with racism and inequality. To learn how local activism can lead to positive change, listen to our audio tour to hear from Crystal Haynes Copithorne, a former Human Rights Commissioner and volunteer here in Arlington.

Project Credits